By Molly Graham, MEEA and Carol Harley, E4TheFuture

Energy efficiency is known for saving money. Although efficiency programs provide much-needed energy bill reductions for households with high energy burdens, a significant number of low-income homes cannot access this relief.

Energy efficiency program services and capacity often fail to align with low-income residents’ needs and the characteristics of community housing stock, and while progress is being made to close the gaps, more change is needed to deliver programs on the scale necessary to meet climate goals.

Investments in low-income homes also offer a myriad of benefits such as:

- reduced energy burdens (the percentage of a household’s income that goes toward energy bills)

- better indoor air quality and comfort

- increased resilience to withstand extreme climate events

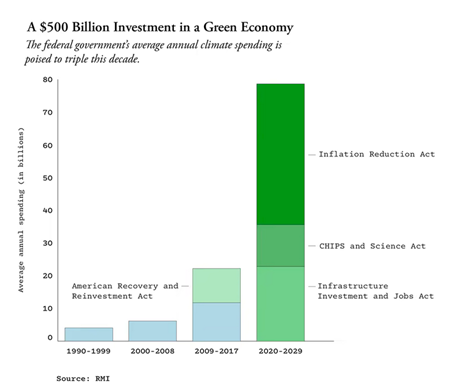

With new federal funding opportunities such as The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the IRA, it’s critically important that program administrators strategically design for maximum beneficial impact in each home. Such designs must address historical underinvestment and inequities.

We are talking about a potentially massive amount of money for “clean energy” writ large, with a significant subset intended for upgrades to homes.

Both the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and utility-funded “income-eligible” programs are plagued by high deferral rates.

What are deferrals?

Deferrals happen when a home is prohibited from receiving services, most often due to safety or structural flaws. Such barriers to weatherization prevent the installation of energy efficiency measures until repair work can be completed.

Deferrals are frequently triggered by issues like:

- roof deficiencies

- moisture and mold

- outdated electrical wiring

- mechanical malfunctions

- the presence of asbestos or vermiculite

The scale of deferrals nationally is not yet known. However, state-level community action agencies have reported encountering deferrals in 15-60% of homes. Starting in 2023, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) will require all 57 WAP grantees to report such data, which will help quantify the need for pre-weatherization funding and programs.

Deferrals and Energy Burden

The prevalence of high deferral rates reveals that substandard housing and energy waste go hand-in-hand. Substandard housing is also a well-documented racial equity issue due to decades of discriminatory lending practices and underinvestment in communities of color. Historical disparities mean that Black, Hispanic, and Native American households experience disproportionally high energy burdens.

Addressing energy efficiency and structural issues for single-family buildings is more straightforward and often less costly than for multifamily buildings. Accordingly, renters are vastly underserved by efficiency and weatherization programs. This issue must receive more attention through policy and stakeholder collaboration to ensure fair access to vital programs offered by utilities and the federal government.

When homes are deferred from a program, their owners must seek other sources of assistance or pay for the mitigation out of pocket. In the absence of discretionary funds, low-income residents are unlikely to incur debt for such projects. If a homeowner cannot afford to fix long standing problems, they are unintentionally excluded from programs that save energy and lower energy bills; and they likely will continue to suffer from health and safety or structural issues.

Addressing the Problem With Pre-Weatherization

Currently, 36 million households are eligible for WAP. Yet the program can serve only 100,000 total homes per year, on average, through DOE and other leveraged funds. At the rate of 100,000 homes per year, it would take 360 years to weatherize all eligible homes.

The industry needs to rapidly scale up the number of homes being weatherized each year. However, the magnitude of homes needing pre-weatherization work lengthens the time frame for homes to receive weatherization.

Simply increasing the funding that goes to the 57 WAP grantees will not decrease deferrals. In fact, when WAP grantees received more funding (2009-2012) the deferral rate increased because the guidance lacked flexibility that would have enabled funds to be used for pre-weatherization repair work. Program administrators need greater flexibility to truly make an impact in reducing deferral rates.

While this context paints a bleak picture of pervasive hazards and missed opportunities, innovative solutions are being implemented at the state and local level. Good examples are Connecticut and Pennsylvania. Each state’s barriers and opportunities depend on their housing stock, resident demographics, available state and utility funding, and workforce.

Best Practices to Reduce Deferrals: For Program Partners

Good first steps to understand programs’ deferral rates and build solutions to target them include:

- Start tracking deferral data. This can help quantify the needs in your community and identify trends which can inform the types of assistance programs needed to deliver pre-weatherization services.

- Explore new funding opportunities, such as federal assistance (e.g., increased LIHEAP leverage) or braiding utility or state low-income assistance program funds. Some states like Vermont have even passed legislation to create new sources of revenue for pre-weatherization funding through new taxes, public benefit funds, or state budget appropriations. The more funding that can be leveraged from non-federal sources, which have strict allowable uses for funding, the more likely the state will be able to increase pre-weatherization services. (See recent legislation on this topic.)

- Develop a coalition of partners to talk through local weatherization barriers and brainstorm implementable solutions. Many states have created working groups of diverse stakeholders to first understand the reasons for their deferrals and then explore new opportunities to reduce them. For example, energy efficiency contractors can play a role within a broader network of community-based organizations, utilities, energy efficiency service providers, state agencies, advocacy organizations, nonprofits and others. There may be opportunities to improve processes across multiple state assistance programs to build a better referral network or “one-stop-shop” program, which can reduce administrative burdens on program management staff and homeowners.

See E4TheFuture’s Overcoming Weatherization Barriers Toolkit and recent MEEA whitepaper for key strategies and examples.

Energy efficiency is a fundamental policy and investment needed to improve resilience to climate change. Recent federal legislation is increasing WAP funding, however this is not sufficient to solve our nation’s substandard housing crisis. We absolutely need smart strategy. If we do not apply funds quickly and effectively, this opportunity could turn into its own crisis.

It is more important than ever that we leverage existing processes of coordination and create new channels to solve the deferral problem. We must increase resources to households needing the most assistance.

Join Energy Efficiency Day 2022 on October 5. We invite you to join hundreds of other people and organization in becoming an official supporter of this annual public awareness event and to check out www.energyefficiencyday.org for more energy-saving tips.

Recent Comments